Eulogy for Lulu: 2003—October 2018

In Memory of My Mother

Patrick Kavanagh

I do not think of you lying in the wet clay

Of a Monaghan graveyard: I see

You walking down a lane among the poplars

On your way to the station, or happily

Going to second Mass on a summer Sunday -

You meet me and you say:

“Don’t forget to see about the cattle -”

Among your earliest words the angels stray.

And I think of you walking along a headland

Of green oats in June.

So full of repose, so rich with life -

And I see us meeting at the end of town

On a fair day, by accident, after

The bargains are all made and we can walk

Together through the shops and stalls and markets

Free in the oriental streets of thought.

O you are not lying in the wet clay,

For it is harvest evening and we are

Piling up the ricks against the moonlight

And you smile up at us, eternally.

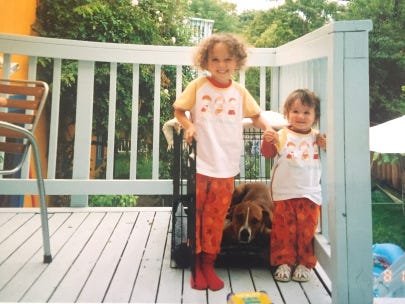

Lulu lies outside now, curled up on her side, her nose between her elegant paws, her well-formed, graceful body curved in a long “C.” Our daughter Nora says, “that’s not Lulu, Lulu wasn’t that body.” She doesn’t like to think of Lulu there, in the tidy rectangular cavity Michael dug gravely, just beyond the ancient plum tree and close to the adolescent plum that grew from an offshoot of its slowly dying mother. Irish poet Patrick Kavanagh wrote this pained paean for his dead mother, and when we were burying our lovely Lulu days ago the words emerged from Michael’s mouth as he began tipping a shovelful of grayish soil onto her body.

Three feet of dry, clumped, grey earth cover the limbs that were adorned in golden fur, save for the white on her paws and chest and spilling from her forehead to her nose. Her Egyptian eyes are shut, the dark edging that outlined them like kohl and that extended exotically from the outside corner towards her ears—so marked when she was young—faded with age. I pulled her skin taut the morning she died to see if I could see that former self in her. Her lids were low, an opaque moon covering the center of one brown pupil, the other remarkably clear of it, looking at me. What was she thinking? What was she feeling? Was she ready to die? Was she only carrying on for us, as my friend, a vet, said our animals, especially dogs, do; they linger, sensing their owners’ reluctance to let them go, she said. Are we really their owners? Are we not, more aptly, their friends, their caretakers, their students, their children, their brothers and sisters, their parents?

Lulu had been slowly failing for a year or so. In recent months her powerful back legs began to betray her and she was no longer able to vault into the back of our aging SUV. When she was young we had to construct a web of wood where the fence meets the gate because she would scramble over the six-foot structure to get out and chase the neighborhood cats. Well into her second or third year, she would leap up and place her paws on your chest or shoulders in sheer abundant energy and playfulness, frightening some, annoying others, and delighting still others with her exuberant affection. We dutifully enrolled her in puppy training but in class, the teachers would just shake their heads disapprovingly at Lulu’s youthful waywardness which was impossible to contain.

She wore dusty paths into the scraggly, weedy grass of our backyard as she endlessly chased squirrels, mercilessly trampling any shrubs I had planted in a vain attempt at beautification. As the squirrels leaped from one sagging branch to another, just maddening feet above her, Lulu would bark feverishly. She caught one or two of them over the years and quite a few of the rats we have in abundance in West Berkeley. With a quick triumphant snap of her jaws, she’d kill the critter dead and leave it to gather flies. She did the same with the chirping grey gophers that scramble like lightning over the boulders of the Berkeley Marina and Albany Bulb. If she happened to be on-leash—which was rare, since both Michael and I hated to inhibit her freedom in any way—Lulu would nearly rip my arm out of its socket when she spotted these animals darting over the steel-colored rocks. She’d whimper shrilly and continuously until you let her off and then she’d streak across the field towards the hapless creature. Her prize prey were the long-limbed hares that exploded out of the long grass, darting this way and that to escape her teeth. They all did, except for one sickly one that succumbed. We are not politically-correct Berkeley citizens; we let dogs be dogs.

It wasn’t one of the animal adoption organizations I’ve seen there before or since; it was a trio of women in their sixties and seventies who had a few cats and dogs in large cages and corrals. Michael spotted Lulu first, pointed at her and said, “That one’s special.” Having grown up on a farm in Ireland around an assortment of animals and with a mother who reared greyhounds for wealthy Irish and English owners, he knew of what he spoke. (It is the same unerring instinct his mother Nancy had for people, as when she said to him after first meeting me, “She’s a thoroughbred,” which meant “she’s finely-bred and highly-strung and will require much work on your part, dear son.” She was, for better or for worse, right). The witches, in response to our inquiry, told us the beautiful three-month-old was a mixture of Lab, Boxer, Rhodesian Ridgeback and Pit Bull, and then they looked at our baby Nora and four-year-old Adriana and said “She’s not good with children. You can’t have her.” We adopted Lulu in the spring of 2003 from a coven of older women camped out on Fourth Street, Berkeley’s one posh strip of designer stores a couple blocks long.

They would not be moved by Michael’s assurances that this puppy was certainly not aggressive, anyone could see that. Their stonewalling only served to enflame him—and me as well. We went home and I contacted my friend Nancy who agreed to serve as our secret proxy in Lulu’s adoption. It worked; in short order, Nancy returned with the adoption papers in hand, and we cackled over the success of our ruse. And with that, Nancy became Lulu’s lifelong adoring and adored aunt, and Lulu changed the course of our lives.

With Nora in a stroller I’d take Lulu to the dusty dog parks in Berkeley, where she’d invariably get into snapping altercations with other dogs; she was an alpha female through and through. When a dog came around to sniff her she’d get still and stiff before exploding into an angry, admonishing series of yelping barks and quick, clipping jaws. The other dog would leap back from her gorgeous form completely surprised and chastened. She would regularly accompany Michael to his weekly soccer practices—where she would sit patiently on the sidelines until it was her turn to bound around the field like mad—and became the much-loved team mascot. In those first years of her life Lulu needed—and got—as much exercise as possible.

Once or twice on her almost daily walks, she drew blood from another dog’s ear and Michael or I would be obliged to reimburse a vet’s fee to the irate, outraged owner. Even at spacious parks, if there were too many dogs—and highly-strung owners—we’d have to call Lulu away from any canine interactions. To those owners who said smilingly, “Don’t worry, my Fido is very friendly” we’d respond, “Lulu is not. She’s great with humans, though.” (Lulu’s ferocity was not reserved just towards dogs and rodents; once during some friends’ afternoon party to which we’d brought Lulu she did quick work of their three pet chickens. We were mortified). Her peevishness got better with time and had almost completely disappeared in the last years of her life: I couldn’t help but compare her dwindling energy and abating aggression to my own menopausal softening. She’d swerve around other dogs rather than engage in a demonstration of her superiority. No need for it, she knew her value.

When Lulu was three or four we thought she might like a companion and thus adopted a little terrier-chihuahua mix named Junior who looked so much like a miniature version of her that people would often ask if he was her offspring. Junior, who at first anxiously pissed whenever Michael came near him, quietly but utterly adored Lulu. He would ply her with sexual favors, assiduously licking the inside of her ears towards which she luxuriantly leaned her head with closed eyes.

Some years later we adopted a little rascal named Rocket, also a terrier-chihuahua mix of which the City of Berkeley Animal Shelter has many abandoned specimens.

Rocket disrupted the delicate, intimate harmony that existed between Lulu and Junior and proved that the axiom “two’s company, three’s a crowd” is true for dogs as well. Junior became jealous and cranky, and Lulu—who in her middle age had started to mellow—picked up on roguish Rocket’s snappishness and sometimes got crotchety. Between the three of them, things swung easily from testiness to love, though Lulu kept a regal distance from the male dogs’ fervid coupling as well as their squabbles.

A close friend postulated wisely to me after Lulu died when I was sobbing with grief, “You’re mourning the end of your girls’ childhood.” She was right; Lulu’s life paralleled the growth of Adriana and Nora into their young adulthood.

Almost every weekend morning Michael and I would call out, “Time to walk the dogs,” and we’d drive—four humans and one then two then three dogs—to get some fresh air and sunshine. There were the early years for both Lulu and the girls, with Nora holding our hands or in a baby harness. Later the two girls played house in the sand or under driftwood structures or we’d all would watch Lulu swim; she loved swimming and was good at, zigging and zagging as we threw sticks she delightedly paddled for. Later still, as the dogs wound their way around us, we’d pick our way over the slippery seaweed-covered rocks by the bay’s edge and clamber over the construction detritus painted by the Bulb’s homeless population in psychedelic intricacy. We’d do a large circle, making our way across a bridge of stones at the promontory’s end as long as it was not covered by the tide. When the girls got older we’d take long hikes up the cool, dark, steep, forested hillsides of Strawberry Canyon with the dogs running tirelessly and joyously uphill in front of us.

On return drives from our walks, Lulu wouldn’t lie down as the other dogs did but rather sit or stand in the back of the car, swaying with the car’s movement and meeting the breeze from the open windows with her snout while gazing raptly at the passing views. What was she looking at? What was she thinking about? Was she planning her next adventure? Lulu loved to run so much that she ran off several times over the years—disappearing across UC Berkeley campus or the Berkeley Marina or Point Isabel, leaving us frantically searching for her. We’d get a call minutes or hours later from a kind soul whom she’d befriended and who’d read her heart-shaped identity tag. To their kind inquiry, “are you missing a dog named Lulu?” we’d collapse with relief.

Walking alone with Lulu, Junior, and Rocket I’d sometimes see myself as others might: a “dog” lady, which surprised me since I hadn’t grown up in a very “doggy” family.

We’d had just one dog, Dacia, whom we adored and who came to us when I was six and died when I was sixteen. Strangely, Lulu was almost the spitting image of Dacia but was a more evolved incarnation who I can say without hesitation was a spirit guide. I felt quite safe on my solo excursions with the dogs since I could see that even strapping men gave Lulu—with her muscular build and formidable jaws—a wide berth. On our walks, Lulu trotted gaily, or more often cantered far ahead, as I jogged or danced to rap or disco pounding in my headphones. I learned not to become embroiled in long or heated phone conversations—especially with my mother or husband—because she’d invariably use my distraction to disappear on one of her walkabouts. She’d move along quickly, her nose near the ground, ignoring my bossy and emphatic demands to come back. This was true especially going up or down the hill from the Albany racetrack to the beach. She’d disappear into the underbrush, hunting the feral cats or occasional skunk that lived there. She’d wolf down the precious, dainty feline food that had been poured into bowls, ignoring my exhortations not to. The cat-women who were sometimes there refilling the food and water would become apoplectic and I’d apologize profusely while corralling my three dogs as best I could, saying, under my breath, “They’re bloody dogs, what do you expect.” I created an episode of my web series, Bad Muthaz, based on a similar experience which occurred on what I call “Glass Beach “- a former landfill near the Berkeley marina that due to its constant sloughing off of shards of glass and ceramics attracts only the most misanthropic of dog walkers. A woman walking near me informed me my dogs were meant to be on-leash. Her walking buddy then added, “Your dog defecated. You have to pick it up.” I pretended not to understand English and replied in Italian, shrugging and smiling like a fool. It worked until we crossed paths on our return loop and I was speaking loudly in English into my cell phone. They remonstrated bitterly.

The softness of her ears. Her deep, urgent bark. Her watchful, sad gaze that held yours. Her pale, taut belly and the short blonde-white fur on it. How she’d jerk her front paws back if you took hold of them. The delicate grooves that ran along her Achilles heels. The stateliness of her white chest and the two hollows within it into which you could sink your two fingers. Her sensual enjoyment when you rubbed her tummy or just above her tail. How she’d ever so gently take the food you’d hold out in your hand for her, never grabbing it like our other two dogs. How she’d slip her head into people’s relaxed hands as they stood talking in the park or in our backyard or in our home, or gently lean her torso into their legs, waiting for a caress. She was a glutton—dare I say slut?!—for a long petting, except when it involved soap. I don’t want to forget Lulu or anything about her.

When we bathed her she’d stand patiently, appearing to enjoy it as you rubbed shampoo into her lithe body while you assiduously avoided her eyes. But after every careful bath, she would gallop to the backyard and scrape herself against the fence or roll in a frenzy, wiping off the clean and wiping on the scents of the urine-soaked earth. A redolent doggy bouquet was her preferred perfume: when you’d walk by her or even by the mat she slept on a wave of her distinctive, salty, bacterial funk would rise up and hit you like a hammer. In the last year or two of her life, Lulu began wandering restlessly through the house at night, her nails clicking on the wooden floors. Her wakefulness paralleled my own menopausal sleeplessness. Lying awake at night, I wondered what she was searching for on her nocturnal rounds. She became deaf and could not hear us talking to or calling her, though she read our faces with the same rapid ease. On walks, we had to clap to get her attention. She still loved to venture yards ahead of me and the two little guys who stayed by my heels so I’d have to squat down and wait for her to glance back. Only then would she stop and turn around, oh so reluctantly, and agree it was time to go home.

Over the years, when I wept inconsolably over the death of friends and relationships, Lulu would approach me, curious and gentle, and look at me with her almond-brown eyes. I was sure she felt my suffering and quite possibly she did. She certainly assuaged my soul when I tired of my roles as wife and mother. For Adriana and Nora, Lulu was a playmate—and a canine caretaker when my maternal patience ran short. Like them, she could be on the receiving end of my temper when I was exhausted. But whether she intended it or not, and I believe she did, she could lift a bad mood. I’d shout, “I’m taking the dogs for a walk” and pull the door shut loudly behind me, or just as often escape the house quietly in the morning, whistling low for the dogs and supervising them into the car, feeling my insides relaxing as I drove with radio blasting to the Albany Bulb. Watching Lulu move swiftly along the gravel paths or the grass, my irritability and weariness would recede as I moved my limbs in the cool morning air.

After our walk, she’d idle at the back of the car and would not jump in until I’d given her a solid dose of love. Nora affirms that I would return from these walks calm and gentle and expansive. It may be odd to admit but I feel Lulu and I played a range of roles for each other—mother, daughter, friend, even lover—but without the accompanying baggage. I could behave less than optimally and I felt she would still love and value me. We could live joyfully in the moment, without the knowledge of past or future failings. I knew (and remember) more about her than I know (or remember) about, say, favorite teachers or most relatives, save for my husband, daughters, mother and siblings. But then, I knew those teachers only a few years and my relatives I see intermittently. Lulu I lived with for fifteen years, observed for countless hours, and loved and felt loved without reservation.

Lulu was dignity, elegance, compassion, love, and intelligence embodied. She lies in our backyard now, her body descending softly into the earth like Persephone leaving her mother Demeter. She was a friend and a guide. There will never be another like her.

Originally published at https://myralabravastrega.com on October 28, 2018.